Ever since I began practicing martial arts, I’ve heard the same debates over and over about their ultimate purpose—and the fiercest arguments always seem to revolve around Aikido. Let’s try to offer a few pointers on the subject, drawing on and developing a couple of well-focused and insightful opinions.

by SIMONE CHIERCHINI

“Who’s stronger, a tiger or a lion?” my daughter asked me today. I told her that each one minds its own business… There are tough karateka and tough aikidoka, granite-hard karateka and aikidoka who look like they’re dancing. Ranking martial arts is a childish exercise, because the issue is the driver, not the car! If the wine in your own cellar is undrinkable, it makes no sense to blame the grapes…

This kind of reflection—repeated endlessly on social media and over pizza—actually hides a much deeper question, one that concerns the very purpose of martial arts in today’s world, Aikido first of all: what is Aikido for today? Because it seems obvious that if you don’t clearly understand what something is meant for, studying and developing it coherently becomes quite difficult and frustrating, if not impossible. If I need to go out to sea, I’ll take a boat; if I need to climb a mountain, I’ll get boots, ropes, and ice axes. But if I throw myself into open water weighted down with climbing gear, I’m certain to drown—so who should I blame? The boots? So then, what is Aikido for today?

To shape a meaningful answer, let’s draw inspiration from the words of the sages who came before us, starting with Kenji Tomiki, the respected pre-war student of Morihei Ueshiba. Here’s what Tomiki had to say on the subject in an interview he gave in 1982 to Stanley Pranin for Aikido Journal:

“During the Edo Period, the rigorous demands of the preceding “Warring States Period” gave way to a time when the majority of people spent their lives sitting in seiza on tatami mats and drinking green tea. Sitting like that people began to wonder what they would do if something unexpected should occur. It became necessary to develop ways of defending themselves by means of throwing needles or methods of avoiding the thrust of short swords. In such confined situations what was called for was the thing we know as suwariwaza (seated techniques). Generally speaking, of the techniques developed during that long period 1603-1868 more than one-third are said to be seated. Truly, “Necessity is the mother of invention.”

Then suddenly, with the Meiji period, the need for bujutsu just disappeared and the waza (technique) became shaky. This was natural and to be expected, since it was no longer necessary to fight wars. Of course, we have no wars now and we won’t have any in the future either. For these reasons, it is no longer necessary to have budo. “Why then is it necessary to encourage them?, one might well ask. The answer to this question is one that we can get at through educational psychology. Most people today have little need for walking, let alone running. They are weak at climbing mountains, poor at swimming. This is a lamentable state of affairs. They are only advancing their heads. It is necessary to match intellectual progress with physical and spiritual development.

The human heart of spirit (kokoro) is something that gets weaker if it has nothing to do, it needs some sort of stimulation. One must have physical strength and the strong will to live. This is where education comes in. The thing that has been put forth to people all over the world as a training method for building up both spiritual and physical strength at the same time through the power of harmony has always been combat, the fight”. [1]

Three important points not to be overlooked:

- “Necessity is the mother of invention.”

- “With the Meiji period, the need for bujutsu (martial arts) simply disappeared, and waza (techniques) became shaky.”

- “The human heart or spirit (kokoro) grows weaker and weaker if it has nothing to do – it needs some kind of stimulation.”

Translated, in my view, this means that only what is necessary has purpose, function, and real value. It means respecting the laws of nature. It means that whatever is no longer needed becomes “shaky,” that is, lacking foundations – destined to collapse and fall into ruin.

Martial arts understood as pure fighting arts, meant solely for combat, have been archaeology for several decades now. Anyone who indulges in belligerent fantasies while wearing a keikogi washed with the detergent that gives “the whitest white ever” lives in a pathetic illusion – sadly nurtured in the company of other deluded souls who enjoy violent games. At the end of every “war” on the tatami or in the cage, these overgrown toddlers treat themselves to a nice warm shower to the rhythm of Beyoncé coming from the Zumba room next door, then rehydrate with a carefully branded isotonic drink from the coin-op machine next to the attractive receptionist. What war, exactly? In war, people butcher each other and die!

These same people are also quite ready to fool newcomers for money, spreading notions about the supposed terror afflicting our streets and the absolute need to defend ourselves from hordes of attackers allegedly waiting for us around every corner… utter nonsense! Never in human history has the world been safer than in the last 70 years. We have Law, and we have Law Enforcement – even if both could do better. Is anyone seriously suggesting that today we live under greater threat than at any point in past centuries? Are we joking? Have these people ever opened a history book? Sowing fear and insecurity is unworthy of anyone who calls themselves a martial artist and claims to embody the values and honour of martial practice. The statistical chances of being attacked are tiny, close to absolute zero. Spending a couple of decades learning how to defend oneself from this imaginary apocalypse simply demonstrates the existence of serious psychological issues in the individuals concerned.

The plain and simple truth, then, is that today there is nothing truly “effective” one can study, because the conditions for using such skills no longer exist, and because doing so is a waste of time. It serves no purpose! Unless one genuinely wants to experience what sweat, blood, guts, and scattered brains really mean. The belligerent overgrown toddlers mentioned above are welcome to go play war in the Middle East, if they truly wish. There are several fundamentalist movements currently looking for volunteers…

In today’s world, the kind of conflict we face is not armed conflict but a constant, pervasive, and subtle struggle—one woven into the fabric of our society and inseparable from it: the conflict of interpersonal relationships. There are more of us than ever before, and we are more connected than ever before, each of us stepping—daily and continuously—on everyone else’s toes. It follows that any training that has a function and is truly necessary, and therefore aligned with the laws of nature, must now be directed toward providing tools to face the interpersonal battles of the modern unarmed warrior.

I chose to practise and teach Aikido many years ago so I could live as a warrior, not make war—to quote the French Aikido master Stéphane Benedetti:

“Live like a warrior, don’t make war! (…) I’m not a militant pacifist, but I don’t like war. I agree with Sun Tzu: ‘The greatest general has no need to wage war.’ (…) So, living like a warrior? First of all, a warrior is not necessarily a military man or a soldier. It’s not about dressing up as a samurai or sleeping with a sword by your side… For me—and since I am not the reincarnation of Morihei Ueshiba, I cannot speak in his name—it is a path, a process of human evolution toward a higher stage of being. The warrior’s path is dangerous, not because you risk being cut down in a hail of bullets in some heroic act immortalised by photographers, but simply because spiritual defeats are many, and the roadside is littered with those who gave up…” (2)

Since this is the awareness I start from, and because I am clear about the purpose of what I do and why I offer it to my students, I like the techniques of my Aikido—just as I like the work that underpins them. Personal disappointments, the state of the Aikido nation, and other people’s nonsense do not shift my thinking by a single millimetre: Aikido is wonderful, its techniques effective and consistent with its aims—though, like all living things, they can be improved and expanded to meet our new needs—and its place within the world of Budo is clear and well-defined.

That the world of Aikido may contain a tremendous chaos of methods and ideas—and that this chaos may benefit those who wish to build little empires and manage people and capital—does not interest me much. The only thing that matters is being clear about one’s own aims and committing wholeheartedly to achieving them, regardless of what others choose to do.

Why are there poor and oppressed people in the world? Why are those who govern always traitors and murderers? Why is scientific progress so often twisted toward aggression or consumption? I can only do my best within my dojo—my extended family—just as people of goodwill have always done. Let us dedicate ourselves to living the good things we preach; anyone can criticise everything and everyone. Building something, however, is another matter entirely.

How do you handle the real conflict that surrounds us everywhere, every single day of the year? Because if you can knock out Muhammad Ali, I couldn’t care less. But if you can harmoniously manage your micro-community, then your Aikido training makes sense—and you have all my respect.

The photo at the beginning of this post—Facebook’s best profile picture ever—is published courtesy of Antonio Vassallo.

Copyright © Simone Chierchini 2015

All rights reserved. Any reproduction without explicit permission is strictly prohibited.

Notes

[1] Pranin Stanley, Interview with Kenji Tomiki, Aikido Journal, 1982 http://members.aikidojournal.com/private/interview-with-kenji-tomiki-1/ (Retrieved on 21/07/2020)

[2] Benedetti Stephane, L’Aikido È un’Arte Marziale? Aikido Italia Network, (-) http://aikidoitalia.com/2011/09/23/laikido-e-unarte-marziale/ (Retrieved on 21/07/2020)

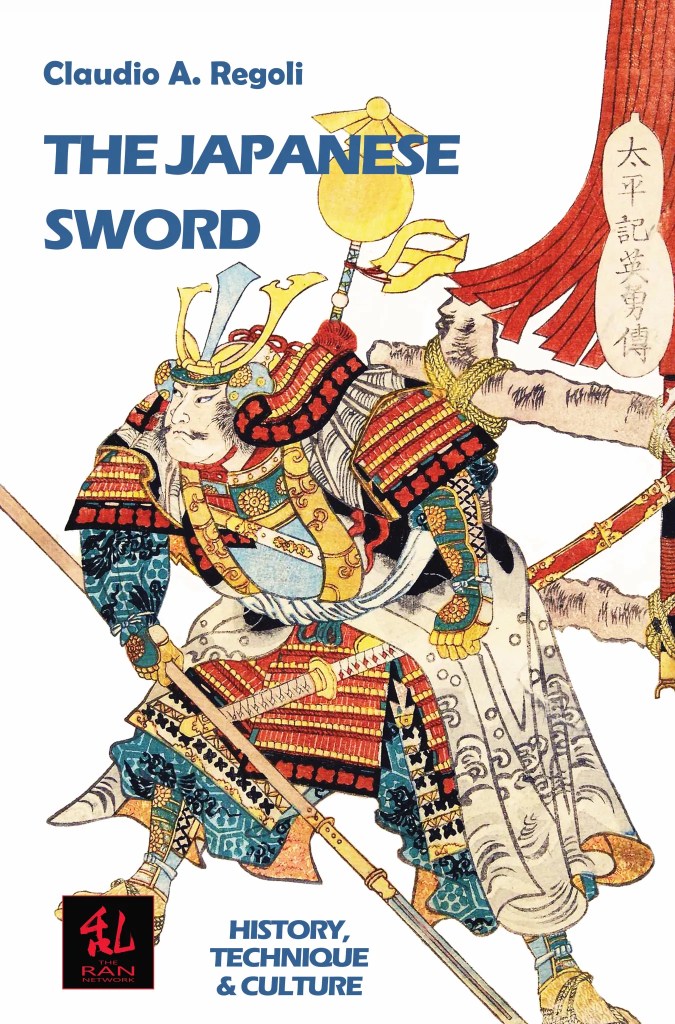

Claudio A. Regoli

The Japanese Sword – History, Technique & Culture

The Ran Network – Historika N. 1

If until recently the admiration for the Japanese sword was confined to collectors and enthusiasts of art objects, the popularisation of martial arts has helped to make its value appreciated by an ever-widening audience. The Japanese Sword – History, Technique & Culture addresses this broader audience, providing a comprehensive guide to the appreciation and evaluation of Japanese sword blades, while also presenting all the necessary background for readers to become part of the circle of connoisseurs in the field.

The text offers a concise introductory overview of Japanese history, essential for understanding the origins and development of the Nihontō, the Japanese sword, before moving on to discuss the myths surrounding its emergence. It then focuses on the history of the sword and its manufacture in Japan, delving further into the characteristics that distinguish the various schools of blade production, their respective swordsmiths, specific production methods, polishing, mounting, and blade testing. Considerable space is also devoted to the technical description of the sword and its constituent elements.

However, no discussion of the sword would be complete without a detailed examination of its use in combat, the result of the work of warrior schools that undertook the study and teaching of how to master the weapon most representative of Japan’s spirit. The author traces the history of the major Koryū, the classical martial schools, and goes on to illustrate the changing role of sword study in modern times with the advent of Dō-type practices and the educational mission of martial arts.