Budo is the world of Mars and has traditionally been the exclusive domain of men for centuries. Although there have always been notable exceptions in the past, it is only after the Second World War that the female presence in the world of martial arts began to be visible. Keiko Fukuda, the only 10th Dan woman in Judo history, was the standard-bearer of this inclusion

by SIMONE CHIERCHINI

Keiko Fukuda (福田 敬子) was the great little woman of Judo. Just 147 cm tall and weighing only 45 kg, this petite woman was nevertheless a giant in the world of Budo. In 2006, the US Judo Federation awarded her the 10th Dan rank, the highest level ever achieved by a woman in Judo (and Budo). This honour had previously been conceded only to a limited number of men. The path Keiko Fukuda walked to reach such a prestigious recognition was, to put it mildly, long and tortuous.

To better understand Keiko Fukuda’s story, it is advisable to go back two generations. His grandfather was a samurai named Hachinosuke Fukuda, an osteopath and a Tenjin Shinyō-ryū Jujutsu master. His name is part of martial arts history as he was the first teacher of the 18-year-old Jigoro Kano, the future founder of Judo. In 1879, a year after Kano started training in the Fukuda dojo, Hachinosuke suddenly became seriously ill and died. Kano continued his studies in Tenjin Shinyō-ryū under the guidance of Masatomo Iso, but was still deeply influenced by the teachings of his first mentor. [1]

This is the family and cultural background of Keiko Fukuda, who was born on April 12, 1913, in Tokyo, in a wealthy samurai family. His father died when Keiko was still very young. The traditional path for Japanese women of the time, similar to their western counterparts, was already set: she was going to marry and have children.

In 1934, when she was 21 years old, Keiko happened to attend a commemoration at the Kodokan Dojo, during which she first learned that her grandfather Hachinosuke Fukuda had been the first and most authoritative master of Jigoro Kano sensei. On that occasion, Kano encouraged her to undertake the practice of Judo: “That was the first time I met Kano sensei. He informed me that there was a new section of Judo for women and encouraged me to join in, telling me that it would keep me healthy and strong. ” [2]

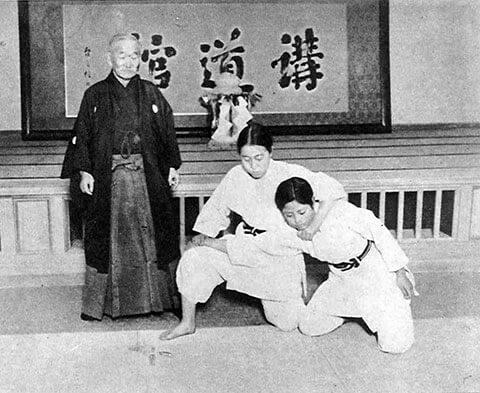

To better frame historically the scope of this decision, which to our eyes appears to be a routine personal choice, Kano’s opening of Judo to women was an extremely progressive scheme in an era in which Judo (and Budo) was dominated by men. From the beginning, Kodokan had been a typically and exclusively male world, similarly to all other arts of the Bugei that would gradually make their way to notoriety in the early decades of the twentieth century. Nonetheless, it must not go unrecognised how Jigoro Kano, further confirming the visionary foresight he already demonstrated in imagining and inventing the world of modern Budo, was also a pioneer in gender equality. The opening of Kodokan’s Women Judo section (Kodokan Joshi-bu), which took place in 1926, in this sense marks a real watershed in the history of martial arts. [3]

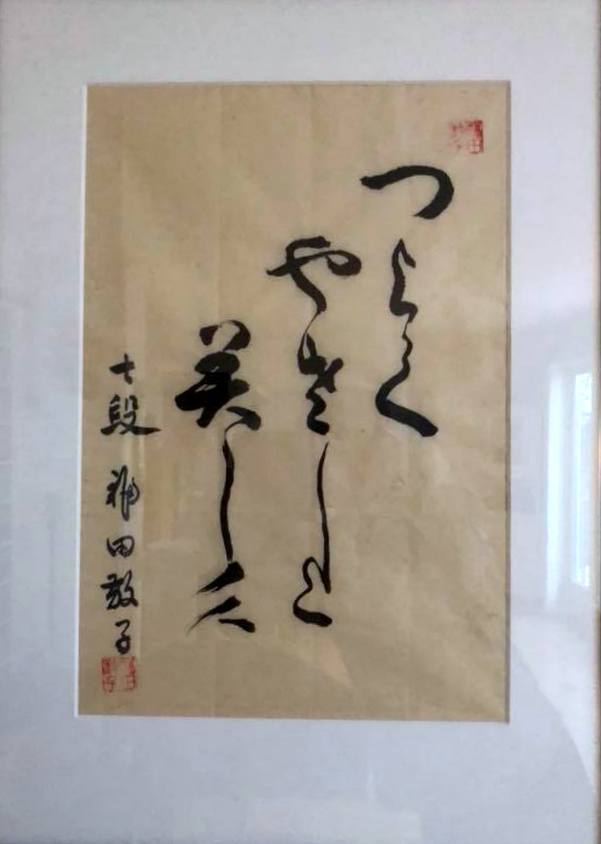

The meeting with Jigoro Kano sparked new emotions in the soul of the young Keiko: The meeting with Jigoro Kano sparked new emotions in the soul of the young Keiko: “At that time, I was only 21 years old, being taught the ways of Flower Arranging, Formal Tea Ceremony and Brush Writing, which was customary for young ladies in Japanese society. (…) Through memories of my grandfather, I felt very close to judo, even though I had never seen judo practiced before.” [4]

A few months after meeting with Kano sensei, Keiko Fukuda decided that she would start practising Judo. When the day came to take part in her first session, Fukuda was accompanied to the Kodokan by her mother: “My mother and brother both supported me, although my uncle opposed the idea because I was a woman. My mother’s and my brother’s thoughts were for me to learn and get married to a Judoka someday, but not to become a Judoka myself.” [4]. At the time women on the tatami were a very rare thing to see. In 1934, when Fukuda started practising Judo, there were only 24 women in the Kodokan [3], compared to a total number of members that, according to Kano, as early as 1922 was in the number of tens of thousands throughout Japan. [5]

The beginnings were far from simple, due to the numerous physical and cultural barriers: “At first, all I could think of was how aggressive the manoeuvres were and how unusual it was to see women spreading their legs”, Fukuda sensei told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2011 [6].

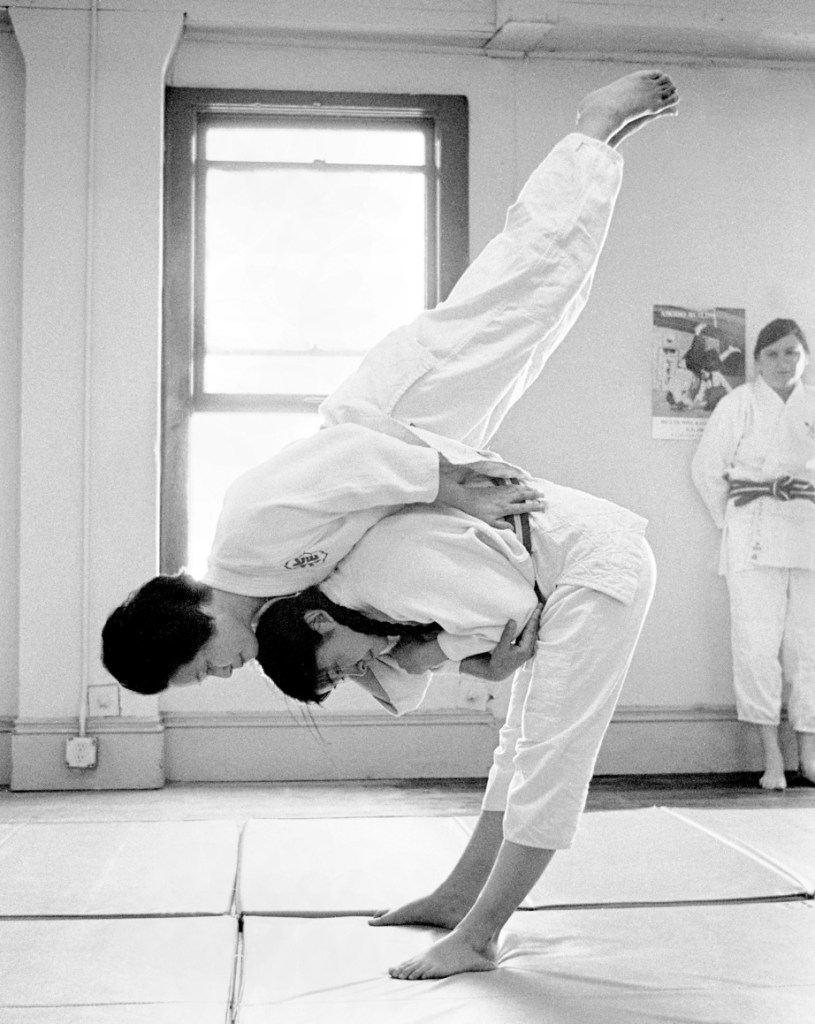

In the book “Born for the Mat: A Kodokan Kata Textbook for Women”, which Fukuda independently published in 1973, the author tells of her training experience at the Kodokan with another Judo giant, Kyuzo Mifune sensei: “I clearly remember until to date that his grip on my judogi was so delicate that I didn’t even feel it. However, if I made the slightest movement in an attempt to throw him, he was no longer where he was before; I, on the other hand, flew through the air. Mifune shihan was small, even for a Japanese (about 160 cm), but his body movements were extremely fast and it was very difficult to keep up with him because he could predict the opponent’s movements and counter him in advance”. [4]

Through constant training and increasing dedication to Judo, towards the end of the 1930s, Keiko Fukuda had become an instructor of the women’s section of the Kodokan and had begun to develop a specific competence in Ju-no-kata (柔の形 ), or the adaptability kata, one of the 7 official Kodokan kata. In the meantime, she also graduated from Showa Women University with a degree in Japanese literature.

At that point in her life, she found herself having to make a decision that would influence the entire course of her future existence. Showing again an independent and courageous spirit uncommon in her time, Keiko Fukuda decided to go against tradition and not to get married. He did this after realizing that, as a married woman, a possible husband would ask her to give up practising Judo, and this was not part of her plans. Kano had inspired his best students to spread Judo around the world, and Fukuda began to consider that this could be the true calling of her life.

Kano had been a visionary who had imagined a future world in which women could – among other things – train on a tatami mat and throw each other exactly like men. However, in 1938 Kano died unexpectedly on the steamship Hikawa Maru, during the crossing back to Japan from a demanding journey he had undertaken in support of Japan’s attempt to host the 1940 Olympics – a journey that had touched the United States, Egypt, Greece, France and Italy. The XII Olympiad was assigned to Tokyo after Kano’s death, but with the outbreak of the Second World War, it was first reassigned to Helsinki and then definitively cancelled.

Kano’s untimely death left for several decades his female students at the mercy of the traditional (and sexist) culture of which the Kodokan Judo was part. The then-dominant conception of the arts of Budo provided only a minimum space for the development of women’s practice, a practice which was viewed with extreme suspicion and at best paternalistically tolerated.

Even during the war, Keiko Fukuda continued to teach Judo daily within the women’s section of the Kodokan. That request by Kano to bring Judo abroad had always remained alive in her memory and finally, after the war, the time became ripe to put it into practice. In the 2012 documentary about her life, “Mrs Judo – Be Strong, Be Gentle, Be Beautiful”, Fukuda offers clear testimony of the above: “Kano sensei wanted us to teach Judo in the world. In the beginning, there were only 5 or 6 of us who had learned English who were willing to do it. In the end, however, I was the only one to do it. ” [2]

Keiko Fukuda first visited the United States in 1953. She had been invited by a Judo club from Oakland, California, and ended up staying in the USA for almost 2 years, after which she returned to Tokyo. In the following years, she made several teaching trips to bring women’s Judo to New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines and Canada.

As a demonstration of her status in the meantime achieved in the field of Judo, during the inaugural ceremony of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Keiko Fukuda was honored to carry out one of the women’s Judo demonstrations together with her senpai Masako Noritomi. The two demonstrated Ju-no-kata. It should be remembered that the 1964 Tokyo Olympics were fundamental for the spread of Judo worldwide, being the first time that Olympic medals were awarded for the discipline. However, this success remained the prerogative of male Judo only, while in a very embarrassing way the Olympic female Judo competitions remained in mothballs for still almost 30 years, that is until the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona.

In 1966 Keiko Fukuda had a new opportunity to teach in California and travelled around the state giving seminars. A demonstration she gave at Mills College in San Francisco ended with a job offer and Keiko decided to stay. A few years and many efforts later, in 1973 she was able to open her own dojo, the Soko Joshi Judo Club, (Women’s Judo Club). [7]

In 1974, Fukuda sensei organized the first Judo Training Camp exclusively dedicated to women. This event then became established under the name of Keiko Fukuda Joshi Judo Camp.

While she lived in Japan, Keiko Fukuda sensei had reached the 5th Dan, a grade obtained in the early 1950s, and had been one of the few women to attain that level. Despite all her efforts and her commitment at national and international level for the diffusion of Judo among women, however, she was no longer promoted for the next 20 years. In the 1960s, in fact, the unofficial grade limit for women’s Judo was 5th Dan. One of Keiko Fukuda’s former students, Shelley Fernandez, happened to be president of the National Organization for Women in San Francisco; Fernandez decided to organize a petition and support letters were subsequently collected and sent to the Kodokan to report the anomaly and to ask that Fukuda sensei be promoted to 6th Dan. The Kodokan understood that times had changed and accordingly Masako Noritomi and Keiko Fukuda were the first women to receive the 6th Dan.

The last symbol of the differentiation between judoka of the two sexes remained in place for several years. Women yudansha wore a black belt like men, but theirs had a longitudinal white band at its centre, as can be seen in some of the repertoire photos of Keiko Fukuda that we present in this article. This use was abandoned by the All Japan Judo Federation only in 2017, i.e. an abysmal 91 years after Jigoro Kano inaugurated his female section of Judo at the Kodokan. [3]

Over the next 30 years, Keiko Fukuda was then regularly advanced to higher grades and received the title of Shihan. In 1990, Emperor Akihito recognized her as Japan’s living national treasure, honouring Fukuda with the medal of the Order of the Sacred Treasury. Furthermore, in recognition of the very long international contribution she had offered to Judo, in 2001 the US Judo Federation granted the red belt to Fukuda sensei, the third ever assigned; the other two had been attributed to men. In 2006 the Kodokan promoted her to 9th Dan, the highest grade ever assigned by the Kodokan to a woman.

Finally, in 2011, when Fukuda sensei had reached the venerable age of 98, the US Judo Federation decided to award her the 10th Dan. Gary Goltz, president of the federation, motivated that promotion with the following words: “Sensei Fukuda is a living legacy, she’s a direct descendent of the origins of Judo, as well as the longest, and only living student of Kano’s worldwide” [8]. The Kodokan never confirmed the grade.

In her later years, Keiko Fukuda was forced into a wheelchair, nevertheless continued to teach at her Soko Joshi Judo Club in San Francisco three times a week. With a total devotion to her art, Fukuda sensei remained as a point of reference for female judoka of all ages until the end, which took place on February 9, 2013, a few days before her 100th birthday, and after having lived life in respect of her motto: “Be strong, be kind, be beautiful“.

Copyright Simone Chierchini ©2020

All rights reserved. Any unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited

Notes

[1] Adams Andy, Master Jigoro, Black Belt Magazine, Issues 02/1970 & 03/1970, in http://www.kodokanireland.com/about/index (Retrieved 12/06/2020)

[2] From the documentary “Mrs Judo – Be Strong, Be Gentle, Be Beautiful”, Flying Carp Productions, 2012

[3] Roy Tomizawa, Keiko Fukuda and The White Stripe in the Black Belt: A Symbol of Gender Discrimination in Judo Fades to Black, The Olympians, 2017 https://theolympians.co/2017/03/22/keiko-fukuda-and-the-white-stripe-in-the-black-belt-a-symbol-of-gender-discrimination-in-judo-fades-to-black/

[4] Fukuda Keiko, Born for the Mat: A Kodokan Kata Textbook for Women, Keiko Fukuda Publisher, 1973

[5] Watson Brian N., Judo Memoirs of Jigoro Kano, Trafford, 2008

[6] William Yardley, Keiko Fukuda, a Trailblazer in Judo, Dies at 99, The New York Times, 2013 https://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/17/sports/keiko-fukuda-99-a-trailblazer-in-judo-is-dead.html (Retrieved 11/06/2020)

[7] Kathleen Sullivan, A Lifetime of Judo: Keiko Fukuda, San Francisco Chronicle, 2003 https://judoinfo.com/fukuda/ (Retrieved 11/06/2020)

[8] https://abcnews.go.com/Health/98-year-woman-receive-highest-degree-black-belt/story?id=14274097

Aikido Italia Network è uno dei principali siti di Aikido e Budo in Italia e oltre. La ricerca e la creazione di contenuti per questo nostro tempio virtuale dell’Aiki richiede molto tempo e risorse. Se puoi, fai una donazione per supportare il lavoro di Aikido Italia Network. Ogni contributo, per quanto piccolo, sarà accettato con gratitudine.

Grazie!

Simone Chierchini – Fondatore di Aikido Italia Network

Aikido Italia Network is one of the main Aikido and Budo sites in Italy and beyond. Researching and creating content for this virtual Aiki temple of ours requires a lot of time and resources. If you can, make a donation to Aikido Italia Network. Any contribution, however small, will be gratefully accepted.

Thanks!

Simone Chierchini – Founder of Aikido Italia Network

[…] Mrs Judo: Keiko Fukuda and the Long Path to Female Inclusion in Budo […]

[…] Keiko Fukuda and the Long Path to Female Inclusion in Budo, Aikido Italia Network, 2020 https://simonechierchini.com/2020/06/13/mrs-judo-keiko-fukuda-and-the-long-path-to-female-inclusion-… (Retrieved on […]